Today, acclaimed poet and author, Stephen Whiteside shares his secrets on writing rhyming verse.

Tips for Writing Rhyming Verse by Stephen Whiteside

When I was young, my father introduced me to the poetry of Banjo Paterson. Later, I discovered the poetry of C. J. Dennis. Both of these poets write rhyming verse or, as it is sometimes called, ‘bush verse’.

When I was young, my father introduced me to the poetry of Banjo Paterson. Later, I discovered the poetry of C. J. Dennis. Both of these poets write rhyming verse or, as it is sometimes called, ‘bush verse’.

This comes from the idea that these poems were often recited from memory ‘around the campfire’ in the days when there were no computers, radios or TVs, and newspapers were few and far between. Bush dwellers, like shearers and drovers, had to make their own fun. Even a guitar was too bulky to take on a long trek ‘outback’.

Bush verse often tells stories. The wordplay of the rhyme is great fun, but the poetry is about much more than the rhyme – it also about the ‘metre’, or rhythm. In fact, this is even more important than the rhyme.

Here are some tips to writing rhyming verse.

1. Read some examples of classical ‘bush verse’ to familiarise yourself with the genre. Some classic ‘Banjo’ Paterson poems can be found here and here. A very famous poem by C. J. Dennis can be found here:

- Give some thought to the rhyming pattern that you want. The rhyme that stands at the end of the first line is traditionally called ‘A’, because that is the first letter in the alphabet. If the end of the second line rhymes with the end of the first line, it is also designated ‘A’. If not, it is designated ‘B’. AABB is probably the most common rhyming scheme employed. It is also one of the easiest to write. These lines with matching rhymes are called ‘rhyming couplets’, for obvious reasons. Another popular rhyming pattern, though it is much harder to write, is ABAB.

- Remember that rhyming verse is not just about rhyme. It is also about rhythm, or ‘metre’. When you have written two rhyming lines, read them both out aloud. Does their rhythm match? If not, you might have a problem. I find that a good way to check this is to tap my foot, or slap my thigh, while I read out the words.

- You don’t have to tell a story when you are writing rhyming verse, but it is a good way to begin. Also, don’t feel that you need to know how the story ends before you put pen to paper – or start to type. Often the only way to find out how a story ends is to start writing, and see where it takes you. Don’t worry, too, if your first poems end up a bit of a mess, or you don’t know how to finish them. The more you practise, the better you will get.

- Your patterns of rhyme and rhythm can be as simple or as complicated as you wish. It is entirely up to you. You might start out with simple patterns, but become more ambitious as you gain in experience and confidence. It is important, though, that there is some sort of pattern to the verse, and that you find a way to communicate this effectively to the reader.

© Stephen Whiteside

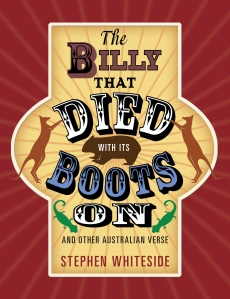

THE BILLY THAT DIED WITH ITS BOOTS ON

THE BILLY THAT DIED WITH ITS BOOTS ON

I was drawn to this book not just because I love bush poetry. It appealed to me because it’s different and it’s funny and it’s very Australian.

It introduces readers to a world and situations they might not have much experience with, but it also shares experiences that kids will connect with.

There are some typical “bush poetry” themes, but they have been brought up to date to engage contemporary children.

The rollicking rhyme covers a huge range of topics from the Australian outdoors, sporting life and animals, as well as the domestic world of the average Aussie kid. – with history and sci fi thrown in for good measure.

For easy reading and reference, poems have been grouped according to topics like around the house, dogs and cats, sport, Australian birds and animals, at the beach, weather, history and Christmas.

There’s often an interesting twist at the end to keep the reader guessing. Here’s an example.

THE ICE-CREAM THAT HURT

I had an ice-cream yesterday,

And, boy, that ice-cream hurt.

Ice-cream’s always good to eat.

It’s taken as a cert!Massive scoops of butterscotch,

And boysenberry, too;

Sort and creamy, luscious, dreamy,

Flavour through and through.I walked a little, licking hard,

And here’s the bit that hurt.

The ice-cream toppled off the cone,

And landed in the dirt.

Lauren Merrick’s black and white papercut illustrations add another lively dimension and stimulus for discussion.

The Billy that Died with its Boots On is the sort of book to be enjoyed at leisure – where you pick out a verse that appeals to you or is relevant at the time. Reading aloud enables you to enjoy the full beauty of the rhythm and language in these pieces.

If Australiana doesn’t appeal or you’re worried that bush poetry isn’t for you, even dinosaurs and aliens feature in this collection.

The Billy That Died with its Boots On is great for classroom read alouds or performances. Poems suit a range of student abilities – some are very straightforward, others are more challenging to perform. This book is for readers 9 +

Dee, I had the absolute pleasure of sitting down and chatting with Stephen last month in Sydney about life and this book. What a refreshing and interesting person he is. I am slowly becoming more enlightened by (or should I say, reintroduced to) the magic of poetry. It’s a lovely sensation. Thank you for this post.

Thanks Dimity:) Stephen and his poetry are worth getting to know aren’t they?

Dee